Scan to see this page on your mobile phone

Scan to see this page on your mobile phoneThe architectural style of Mysore palace is hybrid. That is, its design is a mixture of various schools of architecture. The palace is made in a style collectively called Indo-Saracenic Revival style.

The Islamic power in India by the turn of 12th century has a brought a new style of architecture ( largely central Asian style ) to India.

A large number of Islamic structures in India during the Mughal era were build in the Sassanian ( Persia ) style. So the name Saracenic.

That style when merged with the native Indian styles , gave rise to a hybrid style called Indo-Islamic style or Indo-Saracenic style.

Elements of Hindu styles and Islamic styles merged to form unique school. One good example of this style is the Akbar's abandoned capital Fatehpur Sikri in Uttar Pradesh.

Many centuries later - by the turn of 19th century - India came under the colonial powers. That brought rise to a further new hybrid style called Indo-Saracenic Revival style. Here the Indo-Islamic style is further blended with the Gothic style (,that was the flavor of Victorian rulers) .

Mysore Palace is made in this later style. In other words , one can see the elements of Hindu, Islamic and Gothic elements in its design and construction.

The domes for example is an element borrowed from the Islamic school of architecture. There are many deep pink marble domes projecting at the corners of the palace structure.

To easily understand the hybrid style, take a look at the tallest tower of the palace. This is a five storied tower measuring about 145 feet (45 meters) at the center of the palace.

This projects up from the rest of the roof-line of the palace like a tower of a Gothic cathedral. However on top of it is a large dome, a very typical feature of Islamic/Persian style structures. However it is metal gilded.

Further on top of this dome is a domed Chhatri. That is, a smaller dome supported by slender pillars projecting up from the large dome.

Domed Chhatri is a typical Rajput ( Rajasthani ) architectural feature.

You can spot two more such domed Chhatris at the top on either side of the central arch of the facade. Between these two domed Chhatris and above the central arch is a sculpture of goddess Gajalakshmi. This is a common feature in Hindu architecture as the goddess Gajalakshmi is considered of wealth, prosperity and abundance.

You can spot on the southern and northern extremities of the palace protruding balconies. These resembles that of the 'jharokha' one find in the Rajshani architecture. The balconies appear three-storied from outside. That is, you can see three rows of tall windows one over the other on the balconies. Top of the balcony is with deep pink stone , that forms a semi dome, while the bottom is supported by a structural feature in the form a lotus.

Though each of these features are 'cut and paste' from various types of architectures, on the whole this does not look like a hotchpotch design at tall. On the other hand this hybrid tower adds to the very character of the aesthetics.

As a visitor you enter the palace building through a smaller verandah located at the southern side of the palace.

When you look the palace from the facade , you can see the big central archway ,that is the main entrance to the palace building. On either sides of this large archway are two smaller arches. Further on either sides are 6 arches (3 each on either sides).

The arches are cusped and of Sassanian in origin. These are supported by massive pillars.

The main archway mentioned above opens to a wide passage (elephant gate) that finally leads to the expansive central court. As a visitor you will not be entering through this way. The elephant gate is typically kept closed, baring for the ceremonial functions in the palace.

However during your palace tour you would cross this passage and get a very closer look of the details. The court mentioned above is open to the sky and an enclosed verandah runs around this court. At regular intervals are giant window opening to the court. Also at the three sides of the open court are porches to enter the verandah. You can not enter the court. But the porches and the windows are good enough to get a view of the porch.

The whole court is netted at the top to prevent birds messing the inside. An interesting item you see in this court (flanking the porch) are a set of giant lion images casted out of brass.

Just south of this court is the massive marriage hall (Kalyana Mantapa). This octagonal open hall is brightly decorated. Especially noteworthy are the floor tiles, the balconies , the slender cast iron pillars and the tinted glass ceiling. You can even see some period ceiling fans here ( Mysore city got its first electricity supply in 1908 ).

The whole superstructure of this octagonal shaped ceiling and the pillars were specially made by the legendary Scottish foundry Walter MacFarlane & Co. Ltd. The tinted glasses making a peacock theme over the ceiling were brought from Belgium.

The walls facing this open hall is painted with large oil paintings depicting the Mysore Dasara. Each of the 26 paintings' theme is a function or ceremony related to Dasara . The images are properly labeled and you get the idea of pomp with which it was held. Probably that was the very idea of including such paintings in the palace. That is, to show the king's guests to the palace during those days the details of the festival.

As you move around in the ground floor of the palace , take a look at the pillars, the squinch (where the pillar meets the ceiling ) and the domical ceiling above the verandah. While you will find a great deal of plaster work on the ceiling, the capitals are beautifully carved with hard granite. This too is a present blend of native and gothic styles.

One of the may features where the local traditions of craftsmanship is shown at its best is in the woodwork. You can easily notice this in the massive doors carved out of teak (yellow-brown) and rosewood (coffee colored).

On the rosewood doors,frames and lintels you can see the finely done inlay work. At first it may look like intricate painting on the door. If you look closer, these are ivory chips embedded onto the surface of the rosewood. To protect tampering (by doubtful visitors!) such inlay works are protected with transparent perplex overlay.

Thanks to the lure of attractions below, you may fail to notice the massive woodwork that make the ceiling of some of the portions inside. Take a look at the ceiling when you are in the room that showcased a row of silver and glass chairs. So is the ceiling around the Durbar Hall in the first floor. These woodwork in teak are one of the massive , bold and intricate you find in any palace in India.

As you go up to the first floor , somewhere you would find the Durbar lift. This was operated by mechanical means installed at the roof.

On the first floor there are two major halls. One is for the public hall and the other is a private audience hall.

Durbar Hall ( the Diwan-e-Am ) is a huge open hall along the width of the palace on the first floor. The eastern side is open and gives a panoramic view of the garden in front of the palace. The rows of massive pillars are the special attraction of this hall. On the south and north of the eastern portion are the galleries for the courtiers.

On the western wall of the Durbar Hall is a row of paintings. Most of it is mythical themes from Hindu pantheon.

The private audience hall called Ambavilasa ( the Diwan-e-Khas ) is the most decorative of all the areas in the palace. This is where the golden Throne of Mysore is positioned. It is unlikely that you would find the thrown in the hall unless you happened to visit the palace during the days of Dasara festival. Otherwise the throne is kept in safe custody.

This rectangular hall has an intricately designed tinted glass ceiling. This illuminates the hall lavishly. This light play do wonders on the otherwise brightly painted pillared Durbar Hall.

On the floor , between the pillars are the embedded inlay work - Pietra dura- that is popularly known as Agra work. Various bright semiprecious stones are embedded on the marble flooring to create interesting motifs. On can see a great deal of this work on the Taj Mahal of Agra ( hence the name Agra work).

Like mentioned earlier , the ceiling around this portion has some massive and boldly executed woodwork in teak.

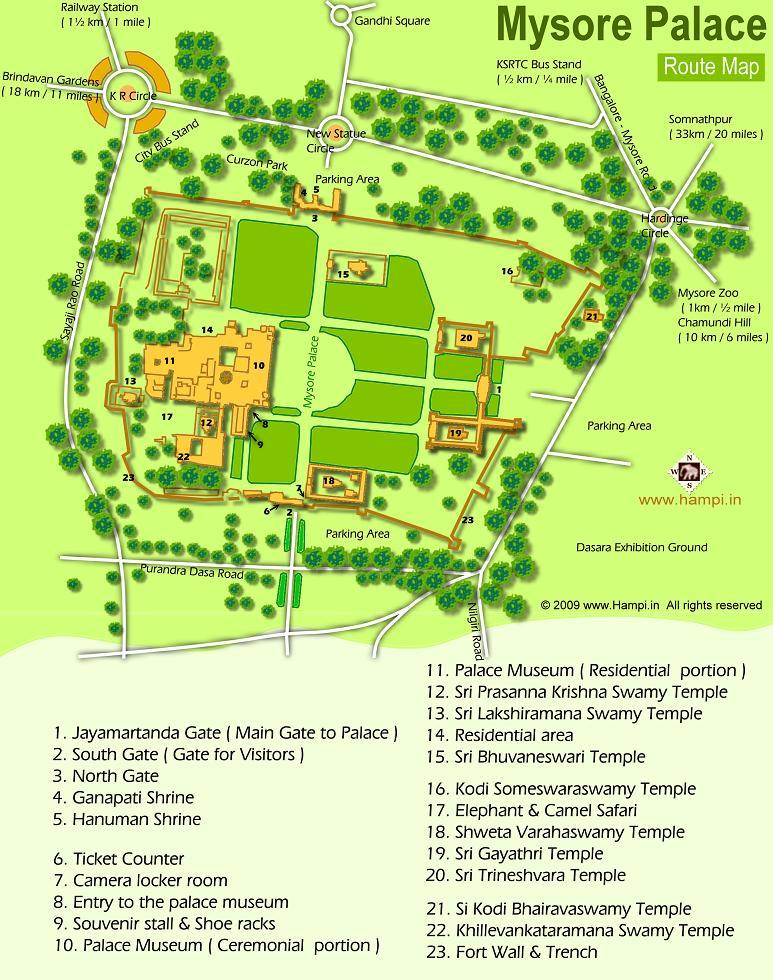

Another important architectural feature of the palace is its gateways and the walls. The one located at the east is the largest of the four gateways. Between the gateways and the palace is a sprawling garden.

Also you can spot a number of temples dotted around the palace campus. The living palace where the family lived is located right behind the main palace. This too is a museum exhibiting a number of artifacts used in the palace. This is made in a more human scale, a lot traditional and can give a great insight into the life of those times.

A little bit of history here on the construction of this palace. The present palace is a relatively new one, constructed over the old palace that was destroyed in a fire in 1897. A model of this destroyed palace is the very first exhibit as you begin the palace tour.

The then regent of Mysore, Maharani Vani Vilas Sannidhna, is credited for constructing the new palace what you see. A famous British architect, Henry Irwin, was commissioned. He is credited with creating many landmark buildings in India . For example the Government Museum,Southern Railway Headquarters, Madras High Court (all in Chennai) ; Indian Institute of Advanced Study,Viceregal Lodge,Gaiety Theater ( all in Shimla ).

In his honor that road that connects Mysore Railway Station to the Mysore KSRTC Bus Stand is named Irwin Road.

In 1912 the construction was completed. Later on in 1940 some extensions were added, most notably the Public Durbar Hall that lies along the facade.

One of the important architectural features under consideration was to make the palace fireproof. So unlike the old palace lost in fire, stone and metal was used for the superstructures instead of the traditional woodwork.

Then there was stress on using locally available materials. The bulk of the palace is made of hard granite brought from quarries around the present day Mysore district.

Most notable is the stone brought from quarries of Turuvekere in Tumkur. They could carve fine details out of it easily. Some of the most elaborate stone carvings in the palace structure is made out of this stone, that was a 'find' during the palace construction.

There was a pan India presence the workforce. That was to bring various type of skills that was required for the execution of a hybrid architecture.

For example masons from many south Indian districts were brought. They even mastered the techniques from the artisans came from places like Jaipur and Kolhapur, known for their speciality in stone work.

There is no better description than the firsthand account of William G Burn Murdoch, a Scottish traveler who visited Mysore in 1905, who witnessed the feverish enthusiasm in which the palace was getting 'crafted'.

Murdoch writes

" Mysore town is a place of wide roads and trees, fields intended to be parks some day, and light and air.

Many houses of European origin,somewhat suggestive of Italian or Spanish villas, are shuttered and closed in, so as to give a sense of their being deserted. You drive past these silent houses and their gardens and come to the native town, which is anything but silent or deserted, and then to the new palace; the modern sight of southern India. It is brimming with life......."

That is the short journey he took from the railway station to the palace.

His accounts were very graphical and detailed enough for one to co-relate with the present day details of the palace. Murdoch continues as he enters the work site of the palace.

"........ it looks like a Gothic cathedral in course of construction. Two towers, each at a guess, 150 feet high,

with a wing between them, bristle with bamboo scaffolding so warped and twisted out of the

perpendicular that the uprights are like old fishing rods. The extraordinary intricacy is quite fascinating,

but at present it partially prevents one seeing the general proportions and effect of the building.

As we see it, in the afternoon, the great mass of building is grey against the western light; thousands

of men, women, boys, and children are scattered over its face on these fragile perches, and though

not in sunlight, their many-coloured draperies reflect on the variously coloured stones at which they are

carving.

Around us, on the ground, are other thousands doing similar work, hewing, sawing, and carving

marbles and granite - such intricate carving - in reddish and grey-green granite. As to the general

architectural effect it would be unwise to venture an opinion at present; but the details are simply marvelous."

From the thick of actions he wonders at what it means to preserving the arts.

"......I believe it is intended to be the finest palace in the world, and if a great many exquisite

fancies put together, will form one great conception, then certainly this expression in architecture must be a

magnificent work of art. The people today and the generations to come must owe this Prince great gratitude

for the encouragement of so many skilled craftsmen, and for the preservation of Indian arts and crafts. "

Then he goes on describing the kind of artisans and their dexterity

"......There were four hundred fine-wood carvers, and four hundred fine-stone carvers, carving filigree ornaments,

chains, and foliage of the most astonishing realism in these materials. Fancy, actual chains in granite, pendants from elephants' heads!

Most of the skilled masons and joiners of India, I am told, have been collected here. The masons must be in thousands;

they are wonderfully skilled in work at granite, their very lightness of hand seems to let them feel just the weight

of iron needed to flake off the right amount from the granite blocks."

One aspect that leaves a visitor spellbound, is the variety of materials that is used in its construction.

Anything from teak wood, to marble, to granite to ivory is used in tasteful ways to make this a charming piece of art.

That is that palace was not made following a standard architectural school. Rather it was

generous in borrowing from various art forms - both Indian and foreign.

Murdoch describes in detail.

" A very much extended description of the Temple of Solomon might give to one who had time to read an idea

of the richness of the materials employed, and the variety of the subjects of the decorations.

There is marble-work and wood-work, silver doors, ivory doors, and rooms, halls, and passages

of these materials, all carved with Indian minuteness and delicacy, with telling scenes from the stories of Hindoo deities;"

Albeit in good humor, Murdoch makes some comments about the cast iron pillars.

".......and in the middle of these Eastern marvels are alas! cast-iron pillars from Glasgow.

They form a central group from base to top of the great tower; between them at each flat they

are encircled with cast-iron perforated balconies. They are made to imitate Hindoo pillars

with all their taperings and swellings, and are painted vermilion and curry-colour. Opening on to

these cast-iron balconies are the silver and ivory rooms and floors of

exquisite marble inlay."

What he explained just above is the Marriage Hall in the center of the palace. This is one of the most

colorful and majestic part of the palace. And also this is the tallest part of the palace. The pillars were from

Glasgow and the tinted glasses on the roof came from Belgium.

Then he goes on comparing the skills of the artisans with respect those at 'home' (Europe).

"We saw inside on many floors, modelers with their clay, modeling groups for the stone-carvers, in high

or low relief, with utmost rapidity, freedom, finish, and appreciation of light and shade. The different methods

of craftsmen in different countries is always interesting. Here the modeler works on the floor seated on his heels;

he runs up acanthus leaves, geometric designs, or groups of figures and animals with a rapidity that would give

our niggling Academy teachers at home considerable food for thought- and yet the work is fine, and the figures are full of expression.

The area of a workman's studio you might

cover with a napkin, or say, a small table-cloth. The carver takes the model and whacks it out in granite

without any pointing or other help than his hand and eye and a pointed iron chisel and hammer,

and he loses very little indeed of the character of the model, in fact, as little as some well paid Italian workers......."

And then he goes on talking about their wages.

"The wood-carving, as far as technical skill in cutting goes, was out and away beyond anything we could

almost dream of at home, and all at 1 shillings and 4 pennies a day, which is good pay here.

One man cut with consummate skill geometrical ornaments on lintels to be supported by architraves

covered with woodland scenes, with elephants foreshortened and ivory tusks looking out from amongst

tree-trunks, and most naturalistic monkeys, peacocks, fruit, and foliage. All this we saw rapidly dug out in the

hard brown teak with delightful vigor, spontaneity, and finish. One might fear that a geometrically carved lintel

would not be quite in keeping with a florid jamb, but why carp, we should look at the best side of things.

I think these same craftsmen working to the design of one artist, or artist and architect in one, might make

a record. The ability to carry out the design is here, and at such a price! But where is the thought, the

conception for a Parthenon- a nation must first worship beauty before it can produce it. "

The wages he described could be a couple of rupees of those times.

To geta better picture of the cost of construction, the estimated outlay of the palace construction of that time was about 4 million Indian rupees ( to be precise 41,47,913 rupees! ) . That's roughly USD 90 000 in present day terms. During that period the asset of the State was around Rs.795 lakhs ( about 79.5 million rupees) and its liabilities to the tune of Rs. 362 lakhs.